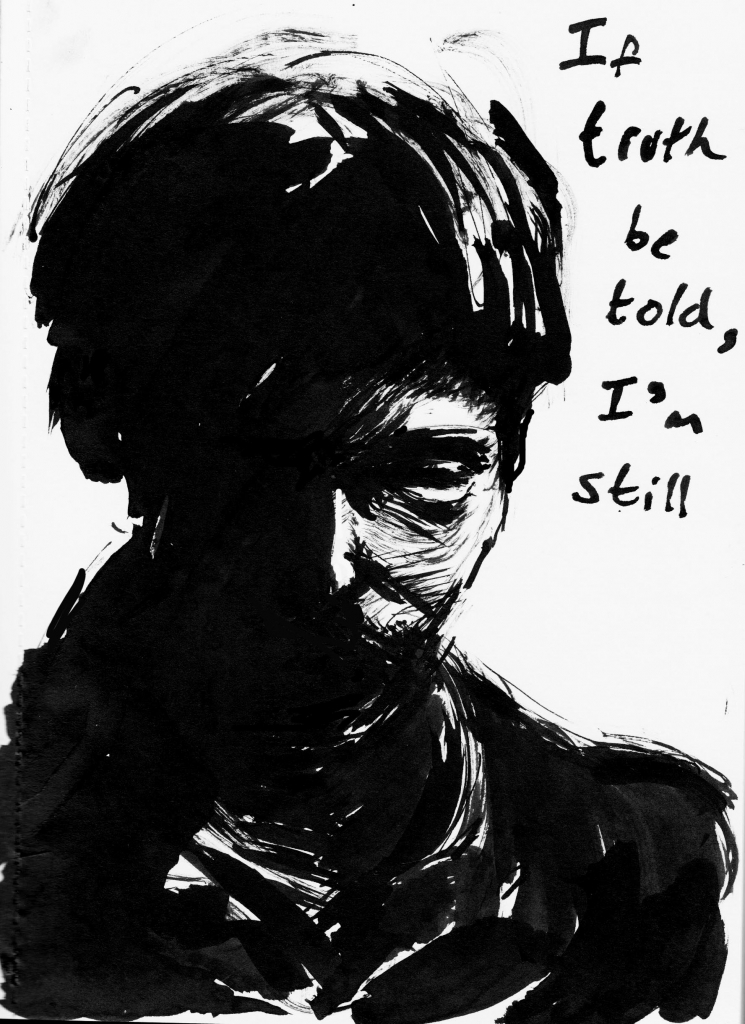

Slight Overbite

by Melissa Ferguson

Your sleeping profile is just like your twelve week ultrasound picture. That little square of paper is more than fourteen-years-old now. I keep it tucked in my purse, behind my library card and in front of a scribbled note to remind me which ink to buy for the printer.

In the ultrasound picture you have a smooth forehead, a button nose and your top lip juts out a little further than your chin. You still have a slight overbite. Of course you’re much larger now. A rash of angry red pimples, yellow heads begging to be squeezed, line your jaw.

The month you were conceived Rob and I were at it almost every day. Every time we went into my bedroom, after smoking pot and drinking Jim Beam in the shed, Mum just turned up the TV. One time we did it on the beach, next to a pile of seaweed. Rob filled the bladder of a wine cask with air so I could have a kind of pillow. I thought Rob very chivalrous, at the time.

❉

You must’ve had a big night last night. You slammed the door when you came in at 3:00 am. You don’t stir when I stroke your forehead. I used to do this when you were a baby and wouldn’t go to sleep. You’d scream at me and bat my hand away until eventually your eyes would droop. When you were older and felt sick, you used to climb into my lap and rest your forehead against my shoulder. I called you my little satellite because you were always somewhere nearby, in orbit around me. Now, I barely touch your shoulder and you shake me off.

Last night Andrea came around and told me something. Something Milly said… about you. At first I apologised—she was upset and she’s my friend. Remember when they moved in across the road two years ago? Andrea and I instantly bonded, a pair of single mums with a string of useless men to complain about. Then I wanted to take the apology back. The movie projector in my head switched on and I saw you as a child, my child, six years old with one front tooth missing, telling me you loved my voice even though nobody else could bear to hear me sing. I thought it can’t be true. You wouldn’t do anything like that. I accused Milly of exaggerating or lying; Andrea yelled and threatened to call the cops. I wanted to talk to you, so you could tell me it’s not true and everything’s going to be fine. But you didn’t answer your phone and I didn’t know where you were. I didn’t want to harass your friends, just because some little girl made up a nasty story about you. Milly probably just has a crush on you. Girls start young these days, with their little jean shorts and nail polish.

I stayed awake and waited for you. Doubts crept in. I remembered when Milly came into the lounge, pouting with that scabby bottom lip she always picks at and said she didn’t want to play in your room. Andrea and I sent her back. We didn’t want her hanging around, we wanted to talk uncensored and unmonitored by little ears.

❉

When I discovered I was pregnant with you, I decided I’d be a good mother. One of the best. My child wouldn’t look back and snigger and judge and blame me for all their problems. I imagined you grown-up, tall and with a face like a young Matt Damon, famous for one thing or another, being interviewed by Oprah. When she asked about your childhood you’d wipe a tear away and say, ‘My mum’s a saint. She had it tough and she raised me by herself. There wasn’t a thing she wouldn’t do for me and I felt loved and safe and supported.’

I was unprepared for motherhood. I thought the intention to be good at it and some kind of maternal instinct would be all I needed. I should have read a book or taken a parenting class or something.

In the hospital, the midwives had me clocked—another young mum from the western suburbs. You cried all night and I asked for help. The nurse strode in from the bright hallway, wrapped you tight and thumped you on the back until you burped. You were a little Houdini when I tried to wrap you, your arms and legs broke free and you screamed and arched your back.

❉

You’ve really fucked up this time. Despite being an unmarried mother, there’s only one other time I thought having you might’ve been a mistake. You were five years old and Aunty Irene had just died. You bounced around the backyard and pretended to dribble the basketball. I sat on the back step and licked an ice-cream cone and you just turned to me and said, ‘I’m not going to die, am I Mummy?’

‘Everyone dies,’ I said.

You stopped bouncing and your eyebrows drew down.

‘But not me.’

I knew then I’d betrayed you when I brought you into this world. There were so many horrific things you were going to have to live through. Terrible things would happen to you, you would experience pain and despair and I couldn’t do anything about it. And one day you’d die. And I’d bear the burden of worrying about you every day for the rest of my life.

‘No. No you won’t die,’ I said, hoping you wouldn’t remember the lie when you were older.

❉

Milly’s just a seven year old girl. Why would you do this? I thought I knew everything about you. Has somebody touched you? A teacher or a friend’s parent? You would have told me, wouldn’t you? Have I raised a monster? Maybe the drugs I took when you were just forming, when I didn’t know you were there, corrupted you. Maybe my pride caused this. I thought I’d be better than my mum, I wouldn’t raise my child in a council house with holes kicked in the walls from biker parties. I read an article on the internet just the other day about how mood swings during pregnancy can affect a child’s mental health. Did I have mood swings while pregnant? I can’t remember. It happened so long ago. Maybe we’d be better off if we grew babies in glass jars where mothers can’t fuck them up with soft cheeses and alcohol and tobacco and mood swings. Then they could be raised by experts, in a sterile white facility set on acres of grassland, so their mother’s parenting mistakes don’t ruin them too.

Maybe this began the moment you were conceived. Some faulty genetics or chemicals. Something from Rob’s side. From the moment you could crawl, containing you was like holding water cupped in your hands; the tiniest loss of concentration and it leaks away and takes any disastrous shape it wants. Then again isn’t that normal for little boys?

I wish I could fix this, stroke your head and say, ‘Mummy’s here, it’ll be ok.’ I hate you because I can’t do that. I can’t make it better and it’s your fault.

This is bad. This is really bad. I wish we’d never met Andrea and Milly, hadn’t spent Friday nights with them drinking lemon squash, with slugs of vodka for Andrea and I, and eating fish’n’chips on the coffee table.

I don’t want you to wake up now. I’ll have to talk to you when you do. We’ll have to figure out what to do. Perhaps the doctor can give us a referral for counselling. Will you be considered a criminal? Will legal action be taken? Will they take you away from me? I’ll have to get on the internet and look it up. What would I type into Google, child sex offenders? I’ll get hold of as much information as I can. I’ll become a world authority on this kind of behaviour. I’ll search out the best treatments and specialists for you. I hope it’s not too expensive. Maybe someone official will step in and put you somewhere where I don’t have to worry about you. Would I be a bad mum if I didn’t mind so much? Will you deny everything? I could just believe you and pretend it never happened. Walk on the other side of the street when I see Andrea, concentrate on the ingredient list on the Coco Pops box when I see her in the supermarket. I don’t know. I just wish you’d just sleep forever, trapped in time, like the ultrasound picture in my purse.

Melissa is an occasionally-lucky-enough-to-be-published author of short stories and creative non-fiction, from Geelong, Australia. She works as a cancer-fighting scientist and is undertaking a Masters in Human Nutrition. Melissa writes when her children are pretending to be asleep. She’s currently finishing a dark fantasy novel called Dandelion Island and preparing to begin a sci-fi novel about a cloned Neanderthal girl. Slight Overbite was sparked by real-life incidences and was her attempt to understand the perspective of a mother of an offender. Melissa blogs about writing at storiesbymelissa.tumblr.com and about food and nutrition at goodfoodbymelissa.wordpress.com.