Lost

by Kit Haggard

When I was a little girl, my parents took me to a town on the coast. It was a capricious summer, heat crackling off the terracotta roofs and pouring up from the pores in the stone. All day, the road to town was slick and wet with sun, but at night, the wind rose off the water and made the shutters slam. The rains came every afternoon and poured with such ferocity that the few little stores closed and a street in the next town was washed into the sea, but the sky always cleared by dinnertime, and it was dry enough on the porch for my father to have a drink and watch the sun set.

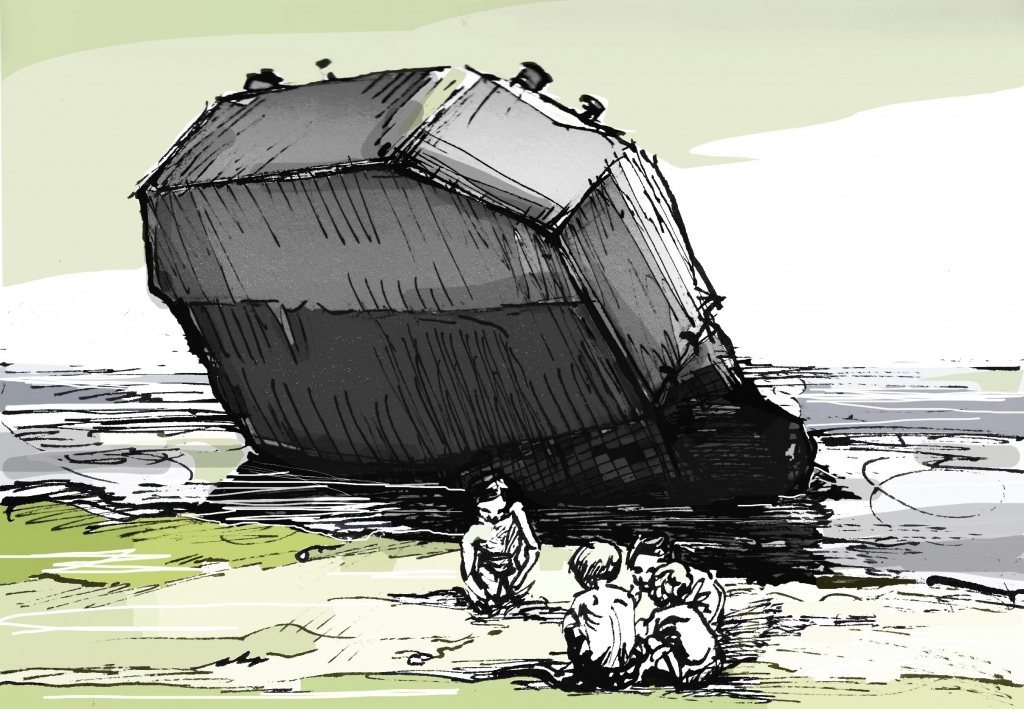

We stayed in a stone house that overlooked the rocky beach and the sloping flanks of the cliffs. Mama was not yet pregnant with my brother, so I could have been no more than six years old, hanging over the rail of the balcony in a flowered bathing suit. There are no photographs from that trip; the camera was left out on the deck in one of the rains and ruined. My memories, though, have a photographic quality to them: bright and clear and fractured. Here is my father in his red shorts, reading the paper on a dock; here is Mama, leaning across a table with the end of her braid trailing salt water; here is the sea around the base of the cliffs, the dark rocks sliced open by the bleached bones of driftwood, my childish certainty that these were the skeletons of whales, the long shadows of the bluffs, and the static sound of the tide.

Two memories have kept their moving pieces. Mama and I stand at the cliffs rising blank-faced from the rocky beach, and Mama says, “Look,” pointing out to sea. I stand on my tiptoes, trying to see whatever has attracted the attention of the gulls, marooned out on some tiny, flat-backed rocked out in the middle of the sea. “It looks like a plane,” Mama says.

“Like the one we flew here?”

“No, love, much smaller. The little ones go down all the time.”

I don’t remember if we ever found out what had wrecked itself against the rocks. Something jutted up from the surface—the accusing finger of a broken wing, maybe, still pointing at the sky—but by the next morning, it was gone.

Mama tells me that my second memory must have been a dream. We talked about it only once, years later, but she said that I could not have possibly remembered the night of the storm. It is the last vivid memory of childhood; everything after began to tuck itself into the ordered drawers where memories may be folded up and kept for years and then taken out to reexamine, like rare maps. Soon after that vacation, my father got sick and filed for divorce from a hospital bed, and childhood was over.

The night of the storm, though, I had a dream that my skin turned to glass, and my stomach filled up with the sea. All my organs had been hollowed out, leaving only my ribs, hanging over the fishbowl of my belly like cliffs. I felt hollow—hollow in a yawning, aching kind of way. Perhaps I was too young to know it at the time, but it was the hollowness of that first stage of loss, when the world seems irreparable and the absence is still new and surprising as the gap left by a missing tooth that you cannot help but poke at with your tongue. It was a feeling I wouldn’t be able to recognize until I was much older, not until it crept up on me years and years later, already familiar, sitting at the bottom of my stomach heavy as a stone. In the dream, I knew only that I was empty, but that the emptiness itself had weight. I watched hermit crabs scuttle across the glass floor of my insides.

When I woke up, I was tangled in the sheets, my six-year-old body thin and damp with sweat. The house we rented was so quiet, and so filled with unfamiliar darkness, that I lay in bed for a long time, holding my breath and waiting for something to make a sound. When nothing did, I went to the window. Later—much later—I would read the Encyclopedia Britannica entry on marine bioluminescence, which, in cold scientific language, reduced what I saw that night to the chemical reaction of flavin pigments in blooming phytoplankton. The sea was lit up with the Northern Lights, breaking waves haloed in St. Elmo’s fire. Everything was blue and green and burning, including the stars.

I crept down to the beach barefoot, in my pajama bottoms with the frogs on them, jumping at every gust of wind through the scrub brush on the side of the road. The afternoon clouds had not entirely cleared, and were beginning to cover the halo of the moon. At the railing where Mama had pointed out the plane, I skidded down the bluff on my heels and tumbled out into the little rocky cove. The stones at the shoreline were all lit up when the tide came in around them. I stood knee-deep in the shallows, making ripples of blue electricity.

It began to rain a bit. The tide began to pull at my ankles and push things up on shore: a stone with a perfect hole through the center, a pacifier, a wooden block with the letter H on it, a bracelet, a shoe, a perfect pink shell like a closed fist, a silver baby spoon. I squatted in the rising tide, water soaking into my pajamas, picking through the rocks.

With the quality of something from a dream, a boat came around one bent arm of the bay, and at the oars, a woman in a red flowered dress carrying a net, lit up by the blue glow where raindrops disturbed the unearthly plankton and scooping the strange debris from the surface of the water. I watched her for a long time, the waves nearly to my waist, as she methodically dipped her net again and again below the surface. Finally, she looked up and saw me on the shore.

“You have to go home,” she called to me. “It’s not safe out here.”

I didn’t move, frightened that I might be in trouble, frightened by the rain, and by the rising swells.

“Go on—back up the hill.”

“Why are these things coming up from the ocean?” I asked, my voice small.

Her boat was tipping dangerously, disappearing sometimes behind the waves. She had to shout to be heard over the wind. “Sometimes things get lost and turn up in the sea,” she said. “Now, you have to go home. Go!”

I was wet to the bone, but I scrambled back up the muddy face of the cliff and ran through the rain back to the house. From inside, the rain sounded like a thousand piano hammers playing on the roof. I took off my clothes and climbed beneath the blankets.

By morning, the clouds had cleared, sunlight coming through the open windows. I woke up covered in sweat or salt; it was impossible to tell. Mama sat on the side of the bed, laying her cool hands on my feverish skin. I’d been sick all night, she said. It had all been a dream. “It’s okay,” she said over and over again, lying down beside me. “Shh, shh. Mama’s here. It’s okay.”

In June of the year I turned twenty-five, my father died. He was in hospice, and not speaking too clearly towards the end. I tried to tell him the story of the night of the storm—that one, final, disordered memory of childhood—but he kept calling the town Macondo, fiction all confused. He died at four a.m. on a Tuesday, Mama asleep in the chair beside his bed, and was buried on Friday. Two and a half weeks later, the man I thought I would spend the rest of my life with followed him into the ground. That emptiness I had known since I was six years old came back and settled into my stomach, blank-faced and expansive, with suitcases full of stones.

Work ended up paying for the trip back to the coast. It had been twenty years, but still the place was stuck in my memory like a bent page; some part of me always knew I’d come back to it. I rented a car in the airport and drove through the mountains toward the sea with the windows rolled down.

Nothing had changed. The same couples seemed to sit at the tables outside the bar—the same boats were tied up and covered with tarps—the same driftwood and brine and static sound of the sea. I parked and unpacked and changed into the red flowered dress Mama had given me as a going-away present, like a reminder that there was still color in the rest of the world. I drank a glass of wine on the porch, watching the clouds come in for the afternoon rains.

“You’re going to get wet if you sit there too much longer.” An old woman stood on the little stone path of the house next door, holding a bag of groceries.

I laughed. “I like knowing that it still rains here every day.”

“You could set your clocks by it,” she said, shuffling a set of keys out of her purse. Her house was small and whitewashed, with a blue door and shutters and a collection of shells pressed into the plaster around the address. Two bay windows looked out onto the street, their sills covered in lace shawls, stones, and pieces of driftwood. In the window closest to my house sat an old camera and a potted fern.

She asked if I was visiting, and I told her about the childish memory of the coast, and my father, and the plane crash that had taken my fiancé. I told her in the voice we save for strangers—too honest, and too matter-of-fact.

“Oh lord, love, you’re much too young for that,” she said.

“It’s—” I couldn’t quite say ‘It’s alright,’ yet. The end of the platitude still lodged in my throat, hard and sharp as a chicken bone. “Well, the little ones go down all the time.”

That night the storm broke; thunder shook me out of bed. It seemed to rattle the glass in the window frames and send change skittering across the top of the bedside table. I lay and listened to it for a while, but it rattled my bones until they were loose in their joints and I had to stand up. It was not raining quite yet, but the thunder-clouds were thick and heavy over the ocean. Their bellies were lit with the electric blue-green of bioluminescence. I pulled on the dress Mama had given me, hanging limp across the back of a chair, and walked down towards the water.

The smell of brine and the bitter, metallic taste of lightning got stronger the closer I got to the water. I walked around the jutting fingers of the docks and towards the boat launch, where the waves broke in glowing eddies against the steep pitch of the shore. Debris drifted in the shallows: keys, gloves, crumpled umbrellas looking like broken-winged birds—all the things we’re used to losing, things that might have belonged to anyone—pens and pencils, socks, train tickets, cell phones, bobby pins, sunglasses. It looked as though somewhere, the crate of loss had fallen from the back of a cargo ship and smashed against the rocks. Soon, though, standing on the boat launch in water up to my ankles, lit by thousands of tiny plankton, I began to see things that could have only been mine: a garnet ring I had borrowed from my mother and lost in a stranger’s bed, a black leather change purse, my grandmother’s collection of crystal perfume bottles, a jar of blueberry jam I bought in Maine and left in a hotel room in the mountains, a set of tiny worry dolls, a paper fan, a burgundy coffee mug, a copy of One Hundred Years of Solitude that I left on a subway, a note from my father on the first page. I pulled the novel soaking wet from the tide and opened it to a random place: “At the beginning of the road into the swamp they put up a sign that said ‘Macondo’ and another larger one on the main street that said ‘God exists.’”

As far out into the luminescent waves as I could see, things I had owned and lost floated on the surface like strange boats. I walked to the end of the dock and watched a photograph of my mother lift itself from the crest of a wave, flutter for a moment, then disappear. I climbed into a wooden dinghy and pushed a little ways out, into the mouth of the bay. There in the water was a t- shirt from a band I could only barely remember loving, a silver flask my brother had given me one Christmas that I had left at a party, a pair of cards from a Mexican bingo deck, depicting el valiente and la sirena. In the bottom of the boat was a net, knots hard and tight as fists, and I cast it over the side and dragged it back, pulling in piles and piles of things I had thought gone forever. I felt a greedy desire to reclaim them all; a sudden, belated fear of someday missing them. Baby clothes, holiday cards, birthday presents; I put the net down again and again, coming around the arm of the bay just as the rain began to start in earnest.

The uncomfortable feeling of deja vu prickled at my skin like static electricity and I looked up. On the shore, partially obscured by the sheeting rain, knee deep in the tide, stood a little girl in pajama bottoms with frogs on them, looking earnestly out to sea. She seemed so fragile and so small.

“You have to go home,” I shouted. “It’s not safe out here. Go on—back up the hill.”

“Why are these things coming up from the ocean?” she asked, her tiny voice barely rising above the storm.

The boat rocked dangerously, rain pouring down and swells pushing over the sides. “Sometimes,” I heard myself saying above the growing roar of the ocean, “things get lost and turn up in the sea.”

Kit Haggard grew up in southern California, but currently lives in New York. Her work has appeared in ASH Magazine, The Mays Anthology, and The Oxford Student, among other places; she is the recipient of the Rex Warner Prize.