Dementia

Annie studies her reflection in the door of Schaeffer’s Gourmet Foods. Her hair is tidy, washed and set. Costume studs sparkle on her earlobes. A department store choker masks the crepey folds at her throat. She mourns her South Sea cultured pearls—three perfect strands with a clasp of round-cut diamonds, consigned to the bottom drawer of her jewelry chest, right below her Birkin bag. At least the Novacheck tote on her shoulder matches her Burberry double-breasted trench coat. Even though it is eighty degrees and sunny, Annie checks her pocket for her fold-up plastic headscarf. It is one of the things she will forget when she cannot remember: To come in out of the rain.

Annie lifts her chin and pushes through the door. The haughty teenage clerks exchange a glance and roll their shadowed eyes.

“Crazy Annie,” they whisper, cracking their pale pink bubble gum.

Annie marches past them, heartened by the whisper of the index cards pinned to the lining of her coat. Yellow cards, on the left side, record names and addresses—her own, of course; her bank and her attorney; her hairdresser and internist; even Trixie’s vet. The right side is more complex, the cards multihued: Blue is for warnings: Look before you cross the street and Don’t eat foods with nuts. Green cards remind her to Tip the doorman when he calls a cab and Take dry cleaning on Wednesday (senior discount). The pink card makes Annie’s eyes mist and she swallows hard. Find Trixie a good home, it says Now, however, she must focus on the task at hand.

Years ago, when Annie hosted formal dinners in the big house on Cherokee Road, this store was called Roy’s Meats. Roy, Sr. kept her in crown roasts and chateaubriand — his glace de veau was superb, his pâté campagne the best she’d tasted since the commune in Gimont — but when he died of liver cancer in 1987, his eldest son inherited the store. Roy Jr. has enlarged it and enhanced it with an artisan cheese aisle and a website. The bright blue awnings and checkered aprons are gone, but the refrigerated cases still hold tender filets, standing rib roasts, and bacon-wrapped pork loin. And Annie’s name—Mrs. Gerald Oscar Phillips—still commands Young Roy’s respect if not his affection.

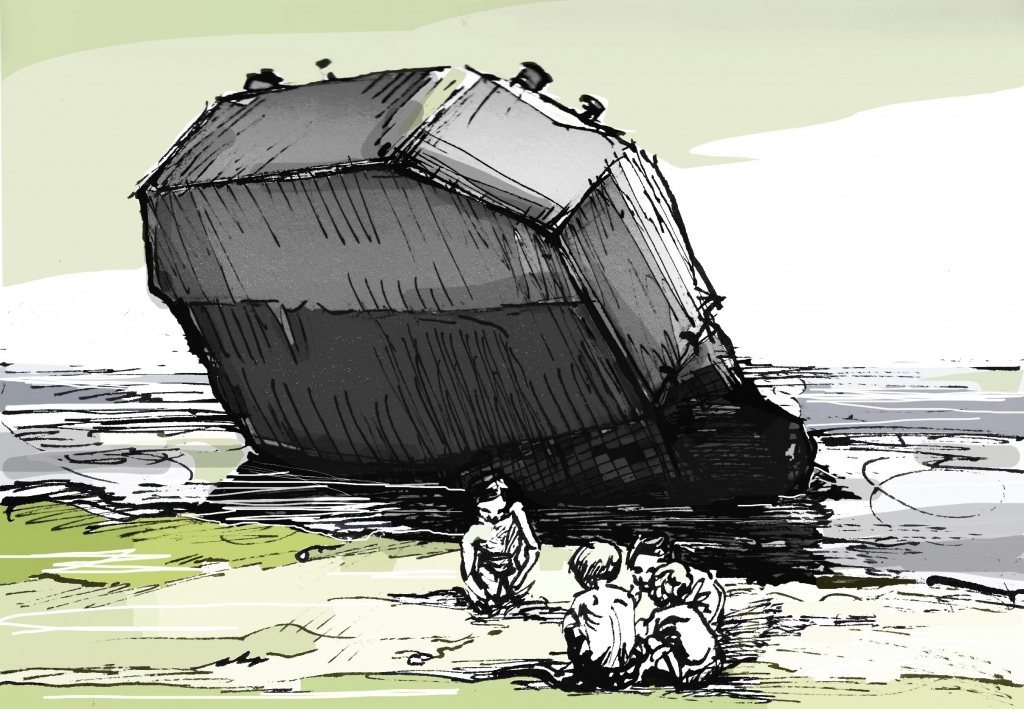

Annie spies him where he lurks among the frisée and artichokes, arranging the bell peppers, bottoms up, pretending he does not see her. She bears down on him like a ship under sail, prepared to grill him: Are the lamb chops lean? Is the chicken free range? Have the greens been triple-washed and wrapped in Earth Friendly paper towels inside perforated plastic bags? Roy loathes her, but how else can she be sure that he will know what she expects, when she no longer does?

Roy’s daughter, the bottle-blonde in the too-tight shirt, has followed Annie to the back of the store as though she might pilfer a jar of chutney or a can of peas. The girl wears a ring in her navel above hip-hugger, bell-bottomed jeans. She snickered last week when Annie asked for French fries when she meant French roast. Pausing by the dairy case, Annie fishes a card from her pocket and writes with the Waterman pen she has kept in her purse for forty years, Next time, shop at Whole Foods, but she won’t. It’s too late.

❉

Annie has seen her internist at ten a.m. on the third Tuesday of every July since 1996, when the Olympics snarled Atlanta traffic. Annie was late, her blood pressure sky high. While Dr. Ginsburg waited for it to settle, he prattled on about his family: Son Matt, pre-med at Duke, and daughter Beth, a summa cum laude Doctor of Economics at Emory, who had joined a think tank in Switzerland. She lives in London, married to a Nobel Prize-winning mathematician named Hobbes. They have a daughter, Elise.

Annie remembers all this, yet last month Ginsburg’s office called at a quarter past ten to ask where she was. Annie, who had managed Gerry’s international travel, three children’s schedules, and a host of volunteer activities, had never missed an appointment in her life. But then, neither did Annie’s mother until she was seventy-three. And so, over Earl Grey tea each morning at eight o’clock, Annie lays out her day in a cramped and slanted script, on monogrammed note pads from the stationer she and Gerry had used for dinner-party invitations. Places to go, people to see, things she must do.

❉

She signs Schaeffer’s tab and requests delivery at four o’clock. Then, alone on the sidewalk, she opens her coat. After Shop for groceries she must Pick up Trixie from the groomer, Buy stamps at the post office, and Have a light lunch of leftover tuna salad on a slice of whole wheat bread with half a navel orange. After a Nap at two for thirty minutes—not every day, just Thursdays because the grocery is a mile from her home and unless it is raining, she walks—she will Do the yoga tape by Susan Winter Ward. That will leave time to dress, comb her hair, and apply fresh lipstick before Eric delivers her groceries.

Eric is a lad of eighteen, a blond body-builder who reminds her of Richard, a lover she took when she was forty and he was twenty-six. Richard had the bluest eyes, the softest hands— and an ego so fragile it cracked like an egg without her daily tributes to his biceps, his buttocks, his…well, never mind. One day he rolled over and propped himself on one elbow. Staring at her rudely, he said, “When I am thirty-six and in my prime, you will be fifty and wrinkled like a prune.” She was tired of him anyway.

While Annie waits for Eric, she sips spring water and nibbles on shortbread with bits of orange peel, listening to the stereo installed by her grandson, an engineering student at MIT. It pleases her to be high-tech, although the system with its sleek cherry speakers— four in the great room, others concealed in the walls of her bedroom and kitchen—cost a small fortune. There is a CD player, an amp, a subwoofer, and a DVD player. Her Sirius subscription allows access to two hundred music channels from satellites orbiting thousands of miles above the northern hemisphere. She likes Classical Voices and Symphony Hall, and sometimes Pure Jazz. Idly she searches the listening guide for a program to fill her newly free Friday afternoons.

“You’re quitting bridge?” Nedda had cried. “Mother, you’ve played for forty years.”

“Forty-two,” Annie corrected her.

Yes, it’s sad, but it can’t be helped. Detailed notes could remind her to take a cab at one p.m. to the Ritz Carlton where they serve crisp lavender cookies; that the redhead with the penciled-on eyebrows is Nancy, the upswept blonde is Lenore, and the blue-haired troll is her partner, Eileen, but Annie cannot scribe a hand of bridge on index cards.

Their club began the year Nedda started high school with Eileen’s son, Jeffrey. Nedda and Jeffrey married in 1981. Their only daughter, Reneé married a Chicago obstetrician; they have three pre-teen children— Robert, the eldest, and twins Katie and Chester. Like Nedda, and then Reneé, they will attend private academies, their tuition paid by Gerry’s estate.

“Will you still come for September?” Nedda asked.

It has been Annie’s custom to visit Sausalito each fall for a month or two, but she answered, “Not this year.”

“We’ll miss your birthday,” Nedda protested. “You can’t celebrate it alone.”

But Annie is not lonely, and at this stage in her life, a distant family is best. Her loved ones won’t detect her burgeoning senility as long as Carter, her attorney, doles out shares of stock for birthdays and generous checks at Christmas. Like Goldman, her banker, Carter is on retainer, with named successors in case either man predeceases her. Both are under fifty, but Carter smokes and Goldman drinks too much.

Tired of the music, Annie switches on a PBS program about the world’s worst dictators. That category should have ended with Hitler and Mussolini. Unfortunately, others—Omar al-Bashir and Kim Jong Il and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad—have risen up to replace them. She will not write their names on an index card. A few things she is happy to forget.

Annie’s conscience prickles as it did the day before, when, in a sweep of her apartment, she discovered her first scrapbook in the back of her sweater drawer. Among the snapshots of slick-haired boys and full-skirted girls leaning against shiny Chevrolets and Buicks, one photograph stood out: A wide-eyed child in a sea of adults laughing and smoking on ornate sofas. At six, Annie had accompanied her mother to Paris to bring home Auntie Jean, her mother’s wayward twin. There Annie had met Gertrude Stein.

Annie does not remember the visit, only the story told to her at age sixteen when her mother gave her the photo to distract her from the war. Annie had immersed herself in Stein and her mentor, William James. Later she devoured Hemingway and Fitzgerald and the Lost Generation, vowing that one day she would have her own 27 rue de Fleurs—though perhaps not a lesbian partner—where she would shelter outcast dignitaries and blackballed artists.

As it always does, life intervened: college, marriage, divorce, and enough lovers to make her blush. Then a second husband and step-motherhood to Nedda, age eight, postponed Annie’s activism. The dry spell lasted until Nedda was twelve and felt called to protest Vietnam. Gerry forbade it—the poor man was a Republican—but Annie took Nedda anyway. On a clear day, in biting wind, they marched along Pennsylvania Avenue toward Capitol Hill, chanting, “One, two, three, four, Tricky Dick, stop the war.”

So much has happened in Annie’s lifetime. Men walked on the moon, others fought for civil rights. The Cold War ended, the Berlin Wall came down, and so did the towers. Meanwhile, Annie joined the hospital guild and the Junior League. She baked cupcakes for the Girl Scouts, led the PTA, and walked for Breast Cancer, three years in a row. She chaired benefits for children, native Americans, and hemophiliacs, always meaning to do more. And now this.

❉

When the calendar in her head began to fail, Annie bought a daily planner, leather-bound and tidy, but soon she grasped the frightening truth: Dates and events can be coached and cued; an entire life cannot. Now, like feathers on a giant parrot, like scales on a rainbow trout, Post-Its cover every surface in her apartment. Notes on her bathroom mirror tell her to Take valium when anxious and Shower daily with Caswell Massey oatmeal soap. On the wall behind Annie’s bed: Your sheets are di Firenze, 800-thread count. You can’t abide satin. Don’t read in bed. On top of the baby grand: You prefer Rachmaninoff to Mahler, Chopin to Debussy. On the refrigerator door: Eat three prunes at breakfast. Turn off the stove. Drink decaf after three p.m.

At four, the doorbell rings. Eric puts away her groceries, pretending not to notice the dust—she has fired the cleaning lady who dared to remark on the “foolish clutter.” Annie’s “foolish clutter” is a priceless guarantee that, when her sensibilities are gone, she will still be who she is. She will not live out her days in a Florida trailer park, watching Jerry Springer and Survivor, eating Lean Cuisine and Double-Stuff Oreos, wearing zip-front polyester tracksuits and Keds with holes in the toes, voting for Jeb Bush. (You are a Democrat. You are pro-choice. But you will NEVER vote for Hillary Clinton for President. Unless Hillary runs against Jeb Bush. God forbid.)

Annie tips Eric handsomely for his discretion and when he is gone, she prepares her dinner: Broil lamb chops, six minutes each side. Microwave broccoli, five minutes on high. And of course, Feed Trixie, although it would be hard to forget since Trixie is dancing the Macarena at her feet. The day is warm enough Annie serves their dinners on her rooftop terrace, where the view to downtown lifts her spirits. Crazy Annie indeed! Her three-bedroom penthouse is bright and airy. The large rooms brim with Regency antiques, Persian rugs, crystal chandeliers, and gilt sconces left over from the big house. The kitchen is gourmet, the bathrooms tiled in marble.

Yet Annie’s rich and varied life has been streamlined and abridged. Her breakfast is the same each day, a soft-boiled egg and a slice of toast. Lunch and dinner vary, but repeat—today she is having lamb chops because it is Thursday. Once a fashion junkie, she clothes herself in lounging pajamas and St. John suits, always in the same order—the crimson tweed, then the navy blue knit with cream piping, followed by the lime shantung and a classic herringbone in brown wool—each stored with matching shoes, scarves, and purses.

Annie has canceled her series at the opera and the symphony, along with her membership at the High Museum. She has culled her magazine and newspaper subscriptions to a favorite few: the Times, Vanity Fair, and Southern Living. All that remains is to sort out the personal keepsakes she cannot bear to part with but cannot leave behind. There are cards and letters she has collected, boxes stuffed with photographs, and treasured mementos like the faded fuchsia blossom that marks the balcony scene in her college Shakespeare text. It takes her back to the second-floor apartment in Philadelphia where she fled after she broke up with Liam, the activist poet. Her downstairs neighbor’s son—Chad, was it? Christopher? Craig?—pinched the bloom from a hanging plant. For three days, they were in love.

Annie has saved her journals for last. There are forty-nine, begun on the urging of a psychologist friend when Annie started chemotherapy nineteen years ago. They fill an entire shelf of her bedroom bookcase—enough for a lengthy memoir. She packs the clothbound volumes in cardboard boxes and writes herself a note: Call the superintendent about incineration.

When she has sealed the last carton with strapping tape, Annie collapses into a deep wing chair. Can it be that she is done? Her eyes sweep the room and land on a card stuck to the TV. Go to bed at 10, it says. It is 10:15 but she isn’t sleepy. She would like to watch the news. Instead, she goes into the bathroom and obeys her own instructions: Change into nightgown (top drawer of dresser). Cream face with Dior Capture. Brush teeth (in circles) with Colgate Extra Whitening—paste, not gel.

Annie slips between the sheets and turns out the light. In the peaceful dark, her eyes drift closed. Yes, she is done. She lies there, content for a moment, and then she bolts upright. What if she goes blind? What if she has a stroke? What if there is a fire? Stop it, Annie, she scolds herself. You cannot prepare for everything that might happen. But isn’t that what she has been trying to do for the past month? Isn’t that what she has done all her life?

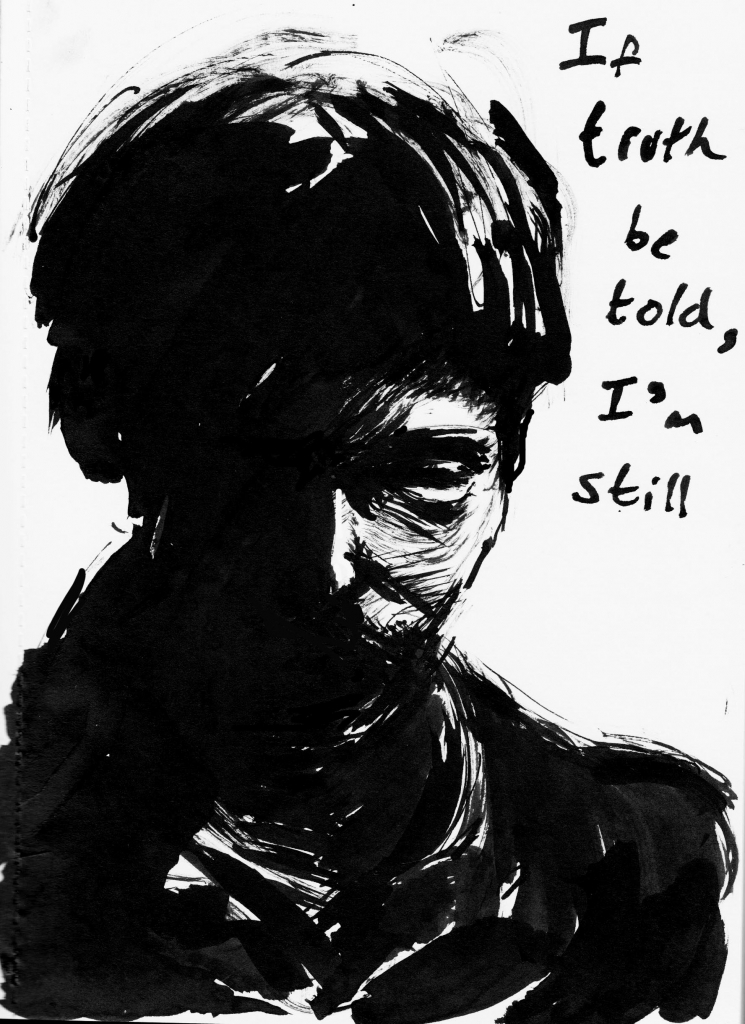

Not long ago Annie would have said she had no regrets. Now she regrets everything: That she ever cared what people thought of her; that she made her choices based on other people’s needs; that she didn’t stay in graduate school, get her Ph.D. and work for world peace; that she didn’t believe she could make a difference and now it’s too late. What Annie regrets most is being afraid—of failing, or looking silly, or doing the wrong thing. And here she is, a slave to fear again.

Annie sighs and flips on the lamp, climbs out of bed, and pulls on her robe. With the scissors on the bookshelf, she slits the tape on the carton she just packed. She pulls out a red-suede journal from 1997 and opens to a bookmarked page. The words astound her; they are lush and magical, deep and brooding, rich and joyful. Annie reads and reads, and finally she understands: If her memories fade like the pigment in her hair, these books will remind her who she is.

A pen and a stack of cards lie on the nightstand. Annie starts to write.

Call Nedda about flights to San Francisco. Get Glenda in to clean. Renew the opera series (Tosca, at least, and Porgy and Bess). Rejoin bridge club. Buy a laptop computer. Start my memoir.

She giggles softly and writes one more line. Next time, shop at Whole Foods.